How would a buddhist respond to the following arguments that critcize the no-self thesis of buddhism?

0

votes

5

answers

180

views

While going across literature pertaining to buddhism, I came across the following write-up named '*Logical Criticism of Buddhist doctrines*' where the author has Criticized various aspects of Buddhist Philosophy.

The question however is meant specifically towards the writer's criticism of the buddhist 'no-self' concept and defense of the soul theory.

While Interested readers might look up chapter 17 (Page 303-326) , for brevity's sake I am summarizing the gist of their main points against the no-self concept and highlighting them for ease of reading.

> **Just as one would not look for visual phenomena with one’s hearing

> faculty or for auditory phenomena with one’s visual faculty, so it is

> absurd to look for spiritual things (the soul, and its many acts of

> consciousness, will and valuation) with one’s senses or by observing

> mental phenomena**. Each kind of appearance has its appropriate organ(s)

> of knowledge. For spiritual things, only intuition (or apperception)

> is appropriate.

>

>

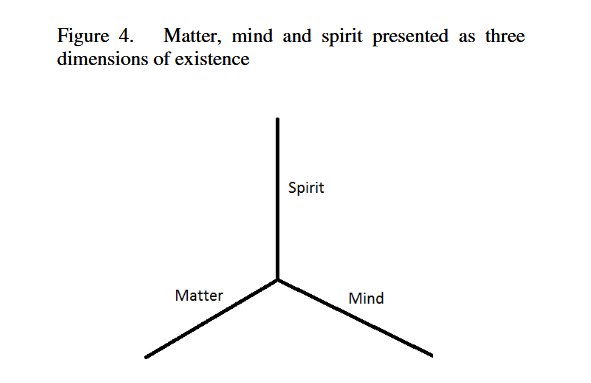

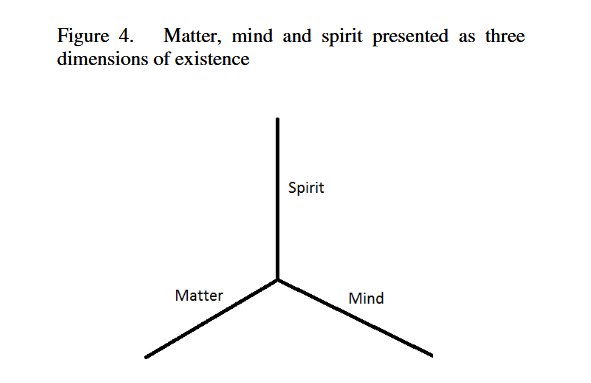

> **To understand how the soul can exist apparently in midst of the body

> and mind (i.e. of bodily and mental phenomena) and yet be invisible,

> inaudible, etc. (i.e. non- phenomenal), just imagine a

> three-dimensional space (see illustration below). Say that two

> dimensions represent matter and mind and the third applies to spirit.

> Obviously, the phenomena of mind will not be found in the matter

> dimension, or vice versa**. Similarly, the soul cannot be found in the

> dimensions of matter and/or mind, irrespective of how much you look

> for it there. Why? Simply because its place is elsewhere – in the

> spiritual dimension, which is perpendicular to the other two.

> **The truth is that it is impossible to formulate a credible theory of

> the human psyche without admitting the existence of a soul at its

> center.** **Someone has to be suffering and wanting to escape from

> suffering. A machine-like entity cannot suffer and cannot engage in

> spiritual practices to overcome suffering. Spiritual practice means,

> and can only mean, practice by a spiritual entity, i.e. a soul with

> powers of cognition, volition and valuation**. These powers cannot be

> equated electrical signals in the brain, or to events in the skandhas.

> They are sui generis, very miraculous and mysterious things, not

> reducible to mechanical processes. Cognition without consciousness by

> a subject (a cognizing entity) is a contradiction in terms; volition

> without a freely willing agent (an actor or doer) is a contradiction

> in terms; valuation without someone at risk (who stands to gain or

> lose something) is a contradiction in terms. This is not mere grammar;

> it is logic.

>

> As already mentioned, **a soul is not an essence, but a core

> (spiritual) entity. It therefore cannot be viewed as one of the five

> skandhas, nor as the sum of those skandhas, as the Buddhists rightly

> insist. It can, however, contrary to Buddhist dogma, be viewed as one

> of the parts of the complete person, namely the spiritual part; but

> more precisely, it should be viewed as the core entity, i.e. as the

> specific part that exclusively gives the whole a personality, or

> selfhood.** This is especially true if we start wondering where our soul

> came from when we were born, whether it continues to exist after we

> die, where it goes if it does endure, whether it is perishable, and so

> forth.

How would a buddhist respond to this critique of the no-self theory?

> **The truth is that it is impossible to formulate a credible theory of

> the human psyche without admitting the existence of a soul at its

> center.** **Someone has to be suffering and wanting to escape from

> suffering. A machine-like entity cannot suffer and cannot engage in

> spiritual practices to overcome suffering. Spiritual practice means,

> and can only mean, practice by a spiritual entity, i.e. a soul with

> powers of cognition, volition and valuation**. These powers cannot be

> equated electrical signals in the brain, or to events in the skandhas.

> They are sui generis, very miraculous and mysterious things, not

> reducible to mechanical processes. Cognition without consciousness by

> a subject (a cognizing entity) is a contradiction in terms; volition

> without a freely willing agent (an actor or doer) is a contradiction

> in terms; valuation without someone at risk (who stands to gain or

> lose something) is a contradiction in terms. This is not mere grammar;

> it is logic.

>

> As already mentioned, **a soul is not an essence, but a core

> (spiritual) entity. It therefore cannot be viewed as one of the five

> skandhas, nor as the sum of those skandhas, as the Buddhists rightly

> insist. It can, however, contrary to Buddhist dogma, be viewed as one

> of the parts of the complete person, namely the spiritual part; but

> more precisely, it should be viewed as the core entity, i.e. as the

> specific part that exclusively gives the whole a personality, or

> selfhood.** This is especially true if we start wondering where our soul

> came from when we were born, whether it continues to exist after we

> die, where it goes if it does endure, whether it is perishable, and so

> forth.

How would a buddhist respond to this critique of the no-self theory?

> **The truth is that it is impossible to formulate a credible theory of

> the human psyche without admitting the existence of a soul at its

> center.** **Someone has to be suffering and wanting to escape from

> suffering. A machine-like entity cannot suffer and cannot engage in

> spiritual practices to overcome suffering. Spiritual practice means,

> and can only mean, practice by a spiritual entity, i.e. a soul with

> powers of cognition, volition and valuation**. These powers cannot be

> equated electrical signals in the brain, or to events in the skandhas.

> They are sui generis, very miraculous and mysterious things, not

> reducible to mechanical processes. Cognition without consciousness by

> a subject (a cognizing entity) is a contradiction in terms; volition

> without a freely willing agent (an actor or doer) is a contradiction

> in terms; valuation without someone at risk (who stands to gain or

> lose something) is a contradiction in terms. This is not mere grammar;

> it is logic.

>

> As already mentioned, **a soul is not an essence, but a core

> (spiritual) entity. It therefore cannot be viewed as one of the five

> skandhas, nor as the sum of those skandhas, as the Buddhists rightly

> insist. It can, however, contrary to Buddhist dogma, be viewed as one

> of the parts of the complete person, namely the spiritual part; but

> more precisely, it should be viewed as the core entity, i.e. as the

> specific part that exclusively gives the whole a personality, or

> selfhood.** This is especially true if we start wondering where our soul

> came from when we were born, whether it continues to exist after we

> die, where it goes if it does endure, whether it is perishable, and so

> forth.

How would a buddhist respond to this critique of the no-self theory?

> **The truth is that it is impossible to formulate a credible theory of

> the human psyche without admitting the existence of a soul at its

> center.** **Someone has to be suffering and wanting to escape from

> suffering. A machine-like entity cannot suffer and cannot engage in

> spiritual practices to overcome suffering. Spiritual practice means,

> and can only mean, practice by a spiritual entity, i.e. a soul with

> powers of cognition, volition and valuation**. These powers cannot be

> equated electrical signals in the brain, or to events in the skandhas.

> They are sui generis, very miraculous and mysterious things, not

> reducible to mechanical processes. Cognition without consciousness by

> a subject (a cognizing entity) is a contradiction in terms; volition

> without a freely willing agent (an actor or doer) is a contradiction

> in terms; valuation without someone at risk (who stands to gain or

> lose something) is a contradiction in terms. This is not mere grammar;

> it is logic.

>

> As already mentioned, **a soul is not an essence, but a core

> (spiritual) entity. It therefore cannot be viewed as one of the five

> skandhas, nor as the sum of those skandhas, as the Buddhists rightly

> insist. It can, however, contrary to Buddhist dogma, be viewed as one

> of the parts of the complete person, namely the spiritual part; but

> more precisely, it should be viewed as the core entity, i.e. as the

> specific part that exclusively gives the whole a personality, or

> selfhood.** This is especially true if we start wondering where our soul

> came from when we were born, whether it continues to exist after we

> die, where it goes if it does endure, whether it is perishable, and so

> forth.

How would a buddhist respond to this critique of the no-self theory?

Asked by user28572

Jan 29, 2025, 10:23 AM

Last activity: Jan 29, 2025, 07:08 PM

Last activity: Jan 29, 2025, 07:08 PM